TO BE ORR NOT TO BE

Budd Orr, they fifty-eight year young Worr Games Product boss isn’t about to retire, and that’s good news for all of us.

BY MATT MARSHALL/PHOTOGRAPHY BY ROM 123

A father sits in his running car, looking past the dash, the steering wheel, he’s boozed, hammered, The engine hums. Light catches the faint emission as it billows in pale blueness.

A son walks up to the to the window. The mother had called to elicit his help. A marriage and a life was crumbling, domestic pieces needed to be picked up and made whole. He carries his father, out to the lawn, stands him up.

“Hey Dad.”

“Hey.”

The son looks at the father, knowing he’s old, knowing help is needed, knowing that as much as he can put forth in this department, it might not be enough.

“You got to lay off the booze Dad.

You’ve got to get some help.”

“you know why I drink.”

“yeah… in the morning I think you should go to a place where you can get help.”

And the Father didn’t want to go, of course-but he went. He went because Bud Orr didn’t want to see the elder part of his father’s life fade away into the drink.

Bud Orr looks the part, 200 plus, odin-like in muscular stature. He looks old school, like there’s a history, a story waiting to be told. He’s big in the way your father was big, larger than life, an authority figure sitting and presiding over his territory without using words to reign, just the sullen and long expression of experience.

But even though his largeness comes across blatantly, he does not wield this as weapon. In fact, as I stand in the Worr Games office a little south of Los Angeles, watch his co-workers bustle about with the day’s activities, watch the shape of an old company transform and morph before me, I smile. This is no longer your average everyday paintball company. Change is here and now. Worr Games is not towing the traditional line, not staying with the stock, simply not content to be average.

The machine shop where the bulk of all Worr Games products are made is not what the 15 year olds in Florida thinks it is. It’s not a huge expanse of building solely made for the company. The shop is housed in a aging industrial complex. Each one of the bays in Bud’s stretch of building was taken over as the company grew, until there were none left, forcing him to get another, larger building, which is just about ready for them to move into, where they will finally have enough room to breathe, spread their wings a bit.

The shop holds remnants of the company’s history, of Bud’s history, and his office is the central hub of busy network of employees. There are pieces of cars and engines through the entire place, machine shop trinkets on casual display in the office. The whole time I was there, the work space appeared communal, filled with people coming to the from meetings, displaying new products for approval, discussing numbers, proposals and dates, all while Bud sat like the sun, his solar system of cohorts gravitating around him in a fixed and complicated clock work. It took awhile for the cluttered chaos of midday business to clear and for Bud to have time to talk. But when we did finally sit down and I asked about his life, about his story, everybody faded away, he took no calls, handled no business other than that of talking about a paintball birth and Autococker legacy.

“I call them redneck,” Bud says about his parents, which comes off a comedic, but he says this with genuine affection. In fact, Bud seems to say everything with genuine affection, like it’s the last time he will ever talk about the matter, like it’s the “According to Hoyle” version of life explanation, which at first you chalk up to the interview and its decisiveness, only, when you hear the reverence in the voices of the people who work for him you understand that this affection is real, genuine. When they speak of Bud and his business, they lean close, open eyes wide, and slow their speech, talking descriptions and wonder and happiness.

“Yeah, my parents were definitely from the old ways, which was fine; it taught you discipline,” he says. He was born in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, but spent 16 years in Miami, leaving for California in ’59, where he was stationed at Travis Air Force base in Northern California, near San Francisco. He had twin boys, Robert and Jeff a little bit after that, when he was only 19. “I grew up with my kids,” he says. It was a mutual growth experience for them, with the boys coming while he was so young, they grew and matured together. The whole time I was at the factory, I never saw Jeff Orr, who run the machine shop. But they way that Bud spoke of him, spoke of the operation, I felt he was always lurking about, Autococker in hand, making things work.

Everybody knows this man for the creation of the Autococker, but what he really was excited about, what nobody knows, it his magic with all things mechanical. The look of the Autococker is a mirror image of Bud’s profession like, a bunch of random pieces put together in seamless working order, making function exist were there was none before. Bud is a mechanical genuine, not by his own reckoning, but by his results. He has spent his entire life making things work, and work well. Cars, motorcycles, airplanes, ships; if it has moving parts, he finds it fascinating enough to tinker with and make sing. He once put an entire car together, by himself, in four days; it was featured in a national magazine profile. A few of his cars have won races.”I’m always trying to make the circle rounded, to make things work better than they already do.” And that is how he got into paintball. His daughter went out to play, came back saying she had a great time

And got her dad out to the field the next week. They Bud bought a gun, modified it, still wasn’t happy and decided to make his own. He called it the DC-9, because it looked like the tail of a DC-9 airplane. It could run on CO2 or compressed air, making it one of the first guns ever to be hooked up with compressed air.

While we were talking, the first sniper ever make, which is the pump predecessor to the Autococker, was leaning Excalibur like, up against Bud’s desk. In a hundred years, if this spot is still around, that gun will probably be worth more than the whole building. But Bud picks it up and shows it to me like it has no significance, like he just built it yesterday, like it’s 1986, and he wants to know what I think. As he goes into the gun’s history, talking about how he assembled the most accurate gun in the history of our sport in eight hours, made it work; He stares long and hard, works the pump action, and you understand why he’s successful, why his workaholic, 20 hour a day ethic has shaped the game I play for living. Advertising rhetoric aside, this piece of metal is function becoming from and I am staggered. Then he tells me he’s dyslexic. And I hold the sniper, take a breath, grasp in awe. A man who took years to learn how to read a sentence, built and designed the base from which the gun was built that has won more world titles and NPPL championships than any other, and he did it in eight hours. Holy Shift.

Of course, it took years to get the gun to where it was ultra-reliable, and that was a immense process in itself, one filled with trial and error, with many people and teams involved. The first gun sponsor of the Ironmen was Worr Games, who Bud said nobody would even touch because they were the “cheatingist sons of bitches you’d ever seen”. But he knew in order to get big they’d have to clean up their act, which they did, and Bobby Long started a great team/sponsor relationship with Bud’s company; the Ironmen were the first Worr Game factory team, in 1990. They Bushwhackers are also sponsored heavily in part because Ron Killborne and Bud have been close friends since 1985.

Tom kayne, who owns and operates Airguns Designs, is a close friends of Bud’s, which is peculiar because the companies have always been fierce competitors in the paintball market, or at least, that’s the public conception of the relationship between the two companies. But the reality is much more interesting. The companies have been closely linked since their inception. When Tom say that Bud was still doing all his design by hand, he gave him his CAD program and showed him how to use it. Bud continues to design his products on it. Tom also helped Bud do his books for a while in the beginning, and they traded ideas constantly, always bouncing to the phone to talk about the next big thing. Bud only gets tense when he talk about the after effects on the Autococker revolution and how in business, imitation is not the most sincere from of flattery, it is the most insulting. The Autococker has been copied by many people, and Bud is quick to point out he’s not rich, just making a good living and building his business. In his mind, all the people who are making their won autococker bodies are stealing from him, and when you look at it from his point of view, he’s right. He’s a man who has been forthcoming in his work, tried to make the best product he could, and other people are copying his ideas, and making money from it. The people who are doing this day it’s the American way, and if you mean legal, then yes, it is legal, so far, but to Bud, a man who has spent his entire career trying to make his inventions better, to make “the circle rounder”, It’s flat out theft. He points out that his company gives back to the players over $400,000 dollars a year to the players, not the promoters. A tour around the factory is a walk through Autococker wonderland. I ask Bud what he thinks about all the electronic markers on the market, if he has any plans to make one or deal with the change in the industry. Sonny Lopez, who is the executive director of the company answers for him with smile, and says, “ Expect big things.” “I can’t make enough of my guns now to meet the demand, so as far as those electronic markers cutting into my sales…well, it can’t be that bad”, and he’s right. They way the industry is now there’s room for both types of markers; both companies are successful, Bud’s brought in a bunch of young, new people into his company, and things new, cutting into the old image of the company with CNC like creativity. Color and shape is no longer constrained by tradition, and with the move into new facilities, the company is shedding its skin, growing up and out. Bud is embracing the new look, the new personnel and talks about his employees like he talks about his own children. They way he runs his business, they are his children, and he keeps them close, but opens up the reigns to new routes. I ask Bud if he plans on retiring any time soon. He looks at me like I don’t know his life, like this choice should be apparent and starts talking about how he could take time off if he wanted to. Bud this man will never stop the race, never lay down, never stand still and say everything’s all right the way it is, it’s just not his nature. He is and always will be a man who tinkers, trying to make things better for the world around him.

THE AUTOCOCKER

THE RANGER

The first industrial approach of the sport

PMI (Pursuit Marketing, Inc.): Pioneering Paintball Markers and Paintballs

Introduction: Pursuit Marketing, Inc. (PMI) is a name that holds significant importance in the world of paintball. Founded in 1982, PMI played a pivotal role in the development and popularization of paintball as both a recreational activity and a competitive sport. In this article, we’ll explore the history of PMI, their contributions to the paintball industry, and the range of paintball markers and paintballs they’ve manufactured.

The Early Days: PMI was established during the early years of paintball’s emergence as a sport. At that time, paintball markers were still in their infancy, and the sport itself was just beginning to take shape. PMI was among the companies that recognized the potential of paintball and played a vital role in its growth.

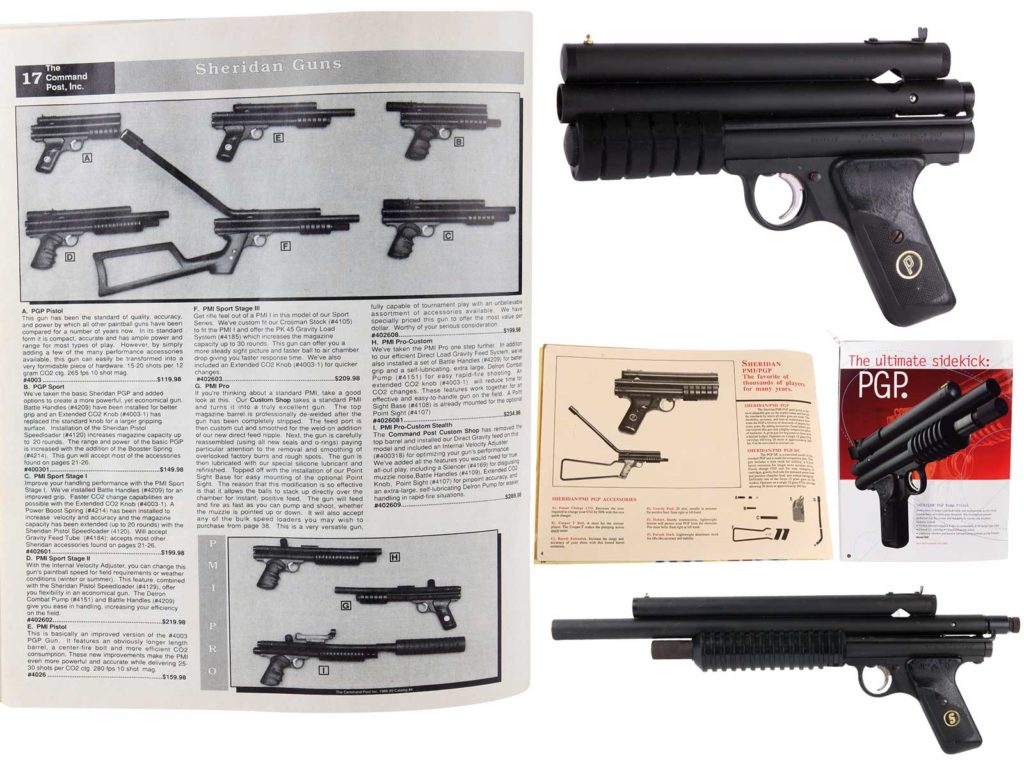

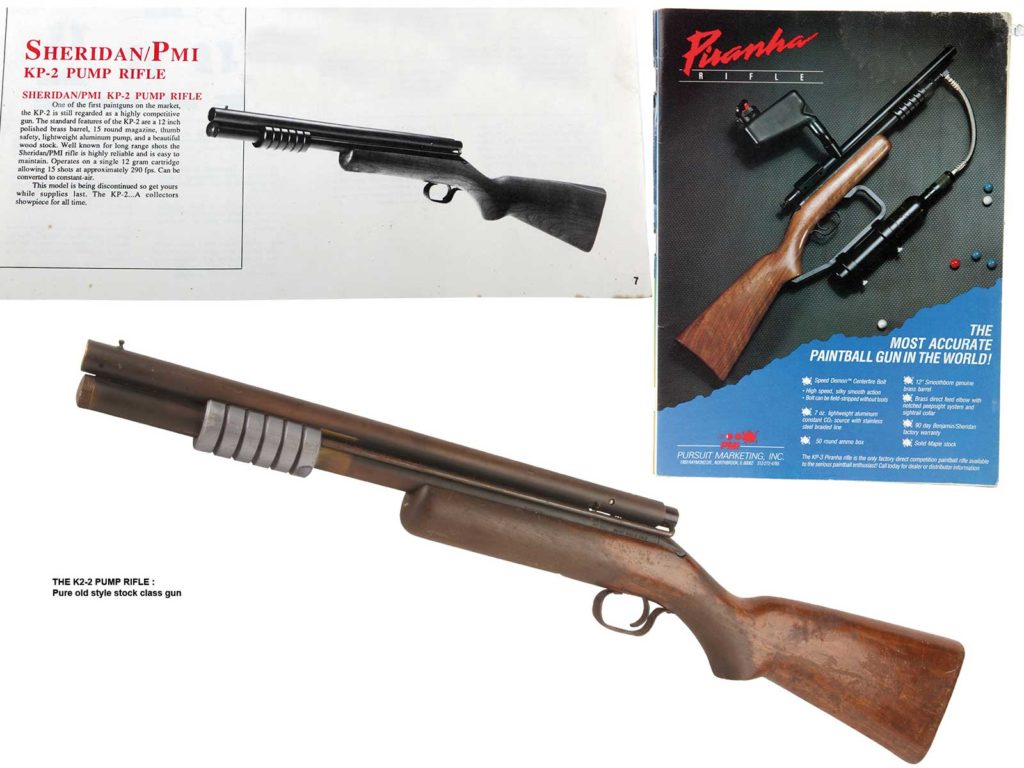

Manufacturing Paintball Markers: One of PMI’s primary contributions to the paintball industry was the production of paintball markers, also known as paintball guns. They developed a variety of markers that catered to different player preferences and skill levels. Some notable PMI markers include:

PMI-3: The PMI-3 was one of PMI’s earliest markers and became popular for its simplicity and reliability. It laid the foundation for future PMI markers.

Sheridan PGP (Pursuit Pistol): PMI acquired the rights to manufacture the iconic Sheridan PGP, a pump-action marker celebrated for its accuracy and durability.

PMI-1: This semi-automatic marker was designed for tournament play, offering improved firing rates and precision.

VM-68: The VM-68 was a semi-automatic marker known for its ruggedness and suitability for both recreational and competitive play.

Paintball Manufacturing: In addition to markers, PMI was also involved in the production of paintballs, a critical component of the sport. They manufactured high-quality paintballs that met industry standards, ensuring consistent performance on the field. PMI’s commitment to producing reliable paintballs contributed to the overall growth and legitimacy of paintball as a sport.

Legacy and Impact: PMI played a pioneering role in shaping the early paintball industry. Their markers and paintballs became integral parts of the sport, enjoyed by players worldwide. Over the years, PMI evolved and contributed to the evolution of paintball technology, leaving a lasting legacy.

Pursuit Marketing, Inc. (PMI) holds a significant place in the history of paintball. Their dedication to manufacturing paintball markers and paintballs helped establish paintball as a widely recognized and beloved recreational activity and sport. PMI’s contributions to the industry continue to be remembered and appreciated by paintball enthusiasts, and their legacy lives on in the ongoing development of paintball equipment and technology.

THE TRRACER PUMP GUN

The Allies rolled several tanks and a fighter plane into the valley, and pointed their cannons up at the Germans

Leaves are shredded and twigs broken in a maelstrom of paint as the 1st Infantry Division unleashes a “surprise” on Omaha Beach-hundreds of men and boys storming across the English Channel with angry muzzles pointed towards the German-held palisades. They carry American flags and roar with hundreds of deep throats overcome only by the sound of action. At 0900, more or less, this coordinated attack commences on three beaches: Sword, Omaha, and Utah, scattered around the D-Day Adventure Park fields.

In keeping with history, the beaches are being attacked from landing craft. One is an actual, floating craft dragged across a pond, while the rest are plywood mockups marooned on the Oklahoma dirt. Several hundred Allies were dropped earlier in the morning on the 210-two hundred and ten acres of additional, undeveloped land-and elsewhere around the 710 acre field.

They massed well behind the German lines, and marched towards objectives decided by Supreme Allied Commander “Psycho” and his War Cabinet. The Germans dug in and waited for the first waves to crest against their trenches, ramparts, bunkers, and other fortifications. The attack would come from all sides, and before it’s over, turn everything a lighter shade of orange-this was their Departure Day in Wyandotte, Oklahoma, and 4,019 players were suited up with orange-fill DraXxus paint in their hoppers. The event set the record; the game set a precedent.

Contact!

The first objectives to fall were the towers on Utah Beach, a particularly merciless stretch of land on the northern end of the field. A half-hour’s walk over rocky, dusty, thick terrain from the camping area, most players elected to ride the deuce-and-a-half “Army trucks” or converted school buses that ferried defenders to the farthest edges of the property. When the Germans arrived at Utah, they found a complicated series of trenches topped with long Oklahoma prairie grass. Wooden bunkers were scattered here and there, with two large lookout towers dominating the skyline to the east. The earth sloped downwards markedly, towards three landing craft in the valley.

Earthen ramparts were augmented with concrete walls and obstructions, anti-landing craft crosses, old military vehicles…the sorts of things one may find on a deserted battlefield long after the salvage has been removed. What they didn’t see were seven Hollywood-quality pyrotechnic charges hidden in the grass. Referees kept personnel away from them.

The Allies rolled several tanks and a fighter plane (mounted atop a jeep) into the valley, and pointed their cannons up at the Germans, of whom there were only 96. Right on time the pyro pots popped with thirty-foot flames, smoke plumes, and thunder. Seven exploded in series, starting the game on an epic note that crashed through the valley. Thousands of markers opened up, spewing more than a case a second into the Oklahoma sky.

Hidden away in the shade nearer to the camping area, is the traditional D-Day invasion spot: Omaha Beach. Several hundred German players, more than at Utah but still under staffed, held fast in a series of trenches cut into a steep hillside. A full size concrete pillbox guards a particularly nasty slope, along with thirty yards of fake barbed wire and obstacles. Two shore-to-ship “gun emplacements” guard the summit of Omaha Beach, and each are worth 100 points hourly from 11:00 to 1:00pm.

This tracks with the other primary objectives, as Utah Beach is worth 200 points at 11:00am and “expires” at 12:00pm for another 200, while Sword expires at 11:00am for 200 points. Oklahoma D-Day is a macro-tactical game, where the tactics and maneuvers exhibited at the company level win or lose the game. Thus, an objective scoring system is used: certain critical components of the field, such as villages, bridges, and “beaches” where most of the Allies insert, are valued in points and given a set time by which the Allies need to have captured them. Un-captured objectives are scored in favor of the defending German team.

Sword beach is the oft-neglected front at OK D-Day. The responsibility of the Commonwealth Forces, this beach is hidden away in the woods between Pegasus Bridge and the village of Caen. Shaded, but smaller and less spectacular than the other beaches, it is nonetheless critical to most Allied strategies: with the bulk of their forces inserted into the game via the beaches, they must fight their way through Sword to attack Caen and flank the southern edge of Colleville.

Worth only fifty points at 1100, the fuel dump in Caen is worth another fifty at noon and a hundred at 1300, making it a 200 point objective, all told. Another crucial aspect of this position is its control of two reinsertion points and an air/paint station. Pegasus Bridge, though not a tactical consideration, is in the immediate area and worth fifty points at 1030-the same as Merderet Bridge in the Vierville Valley.

The other early objectives were the “guns of Brecourt Manor,” along the road between Colleville and the Airfield. The game coordinators dropped the Airborne units far west of Colleville, in the trees where they could choose several avenues of approach behind the German lines. They pushed towards the backside of Sword Beach, and didn’t hit Brecourt as strongly as they could have-the points went completely to the Germans, as did the fifty for Pegasus Bridge.

“We had (fake) barbed wire, mines, everything,” Ryan Smith said. He watched Sean take out nearly forty players with the Double Trouble, in a desperate bid to slow the combined Airborne juggernaut. “It slowed them down some… We were just supposed to stop them from getting to the beaches fast.” And they succeeded.

By 1100, two hours into the game, the Germans still controlled Sword beach and all 200 points it was worth. Not that the Commonwealth wasn’t trying-the German forces had just been marshaled to protect that beach and its connections to Colleville. But the manpower came from somewhere…

As the 96 defenders of the quickly-overrun Utah Beach can attest, lack of German defensive numbers was a significant factor this year. Though not as lopsided as several years ago, the hundreds of Allies attacking Utah found less than a hundred defending Germans. “Oh man,” German Field Marshall Wilhelm Bailey exclaimed from his passing command tank, “it’s another numbers game!” When he clarified his statement later, he noted the light forces on Omaha, Sword, Colleville, and elsewhere. Nonessential personnel were pulled from deep emplacements in the desperate minutes leading up to game-on, to plug the gaps left by phantom players.

Where’d the Germans Go?

One group showed up to play speedball on the complementary speedball fields, Bailey said. “I talked to them, and they said ‘it’s cheaper to play speedball here all week than it is to practice anywhere else.’ They were signed up as German, but didn’t play in the game.” Thus, in balancing the teams during pre-registration, the Germans were credited with that many players, and matched with an equal number of Allies who actually showed up Saturday morning.

Other players were scattered between various units, with no hard loyalty to one group. When their front went quiet, rather than waiting for a strategic defense or redeployment, they’d wander off in search of action, and frequently find their way to the parking lot. But why didn’t they show up in such strength at first?

Despite being assigned to units during pre-registration, many of them felt somewhat adrift among the hundreds of tents and thousands of players. When they loaded up for deployment, hardcore groups like the Geisterjaegers stuck together tightly…and others just wandered into random transports. The Allies had the edge in pre-game unit identity and cohesion, and it showed when the buses rolled out on Saturday morning.

Lunchtime?

By one o’clock, the game was being dominated by motivated, well-marshaled Allied players with a lopsided score of 1,500 to 450. The Allies failed on Sword, but succeeded marvelously on Utah, Omaha, Caen, and in taking Pegasus Bridge an hour after the Germans received the first points for it. While a number of players hopped rides off-field for lunch, most never to return, the vast majority of both teams stayed on the field.

On-field paint sales, via a coupon redemption program, and on-field air fills helped them stay equipped. A number of water buffalos, one in each of the larger reinsertion zones, kept them hydrated. The thirty minutes between reinsertions provided welcome respite after a few hours in the brutal Oklahoma sun. With their goggles off behind the safety netting, players hydrated and traded memories even as the game unfolded yards away.

Then they got back into it, throwing themselves repeatedly at each others’ offensive and defensive lines…and loving it.

More than Saturday

Oklahoma D-Day is more than a one-day scenario: it’s a week-long woodsball extravaganza. Starting on Monday, June 4th, they played paintball-a lot of paintball. In previous years Jeremy Hanna, game coordinator and second in command under D-Day pioneer Dewayne Convirs, watched players sit around for days before the game. Then the game’s command staff had a golden idea. “We’ve had thousands of players sitting around with nothing to do,” he said, “so, why not play paintball? That’s why everyone’s here!” Thus, the “mini-scenarios” were born.

They started with several dozen players early in the week, and had grown to 600 players-in one somewhat formal mid-week game-by Wednesday. Special skills and tactics classes were held, including a qualification course for “Special Forces” players that Wetworkz from Kansas City, MO, facilitated. They’ve built an impressive course with intimidating obstacles for a legendary experience-the closest you can come to Boot Camp training without signing a contract or losing your hair.

Christopher Larkin of Shepherd One-a teambuilding and tactical gaming company-conducted a Small Unit Tactical Leadership (SUTL) Course for Allied commanders. No Germans were invited, though “that would have been cool with me,” he said. It was one of the Allies’ “secret weapons” this year.

A year’s preparations came down to Saturday, June 9th.

Tied Up

This was the tenth anniversary of OK D-Day, as in 1997 field owner Dewayne Convirs held the first one in honor of his grandfather, real D-Day veteran Enos Armstrong. A fair number of people turned out, and since about 2001, D-Day has been setting world records for attendance and duration of a single woodsball event.

And over those years, the Germans have won a few games, and the Allies have won a few games…this year brought the rivalry up to a tie, with five anachronisms and five historically accurate conclusions. The Allied dominance continued long into the afternoon, with the Germans simply unable to keep up this year.

When the scores were announced Saturday night, it was to a crowd of only a few hundred-everyone else was asleep in their tents, their cars, or stretched out on the grass where they’d collapsed from the heat and effort. Word spread, stirring the Allies and deflating the Germans, setting the stage for a solid year of planning by each command staff.

They’ll use the forums again, and in person recruiting; they’ll meet at Woodland Warriors events (promoted by Wilhelm Bailey) and Fledgling Scenarios games (promoted by former Allied Commander Jim Helton). They’ll build more tanks, repaint their old ones, and get second jobs to afford their paintballs.

And in June 2008, you can meet them in the hills of Oklahoma, on your own personal D-Day.